Questions about the role of young and regional universities in the innovative development of their regions lays at the heart of the RUNIN project. Accordingly, they are supposed to stimulate growth and innovation through the active engagement with a wide set of regional stakeholders. This expected engagement presupposes that regional stakeholders and their counterparts at the universities know how to find each other. But, since there are many different actors – SMEs, start-ups, big companies, municipalities, business and civil society associations, students, etc. – with diverse needs and interests, can we build a system where everyone knows “which door to knock”?

Through my fieldwork observations at two universities, the University of Twente (Netherlands) and the University of Aveiro (Portugal), I observed that a great variety of doors, gates, and entry points was created. At the UT, I encountered, amongst others:

- a strategic business development office for the relationship with big companies,

- a Science Shop for the relationship with civil society organisations,

- the intermediary organisation Novel-T for technological start-ups,

- different valorisation and business development managers active in the departments,

- the Science Park “Kennispark”.

In Aveiro, some of the main entry point are:

- the technology transfer office (UATEC) for official contracts with companies and projects related to public funding,

- a business connection office linked to the rectory as well as a vice rector for the contact with companies,

- a science factory focused on the social and educational organisations,

- an incubator at the Creative Science Park,

- a pro-rector for the relationships with municipalities,

- 8 technological platforms with a focus on particular sectors.

So, there is a set of intermediaries at different university levels which are supposed to create links to specific external communities in their direct environment. Thus, the regional partners are expected to know which engagement activity would be in line with which entry point. I see two challenges here: 1) Will regional partners actually be able to find the right entry point? And – if not – 2) Will regional partners that knocked on the wrong door be referred to the correct entry point? According to my experience, the engagement communities are organised in their own way and function very differently, thus we cannot expect them to be able to forward a misguided external partner to the “right” entry point. This happens either because they do not know which gate is the correct one or because they might not know how to engage with the other community.

External actors in both regions suggested to me that there should be only one entry point to the university. These types of solutions – ‘one stop shops’ or ‘one door in’ policies – have also been suggested by policymakers, assuming that they are most efficient. But are they? Perhaps a variety of different entry points is far more valuable, in view of the diversity of regional actors, who are all likely to have different levels of absorptive capacity, different needs, different resources, etc. After getting to know the different engagement communities, I realised that one office might be unable to connect all those different actors and coordinate between those communities that work and communicate so differently.

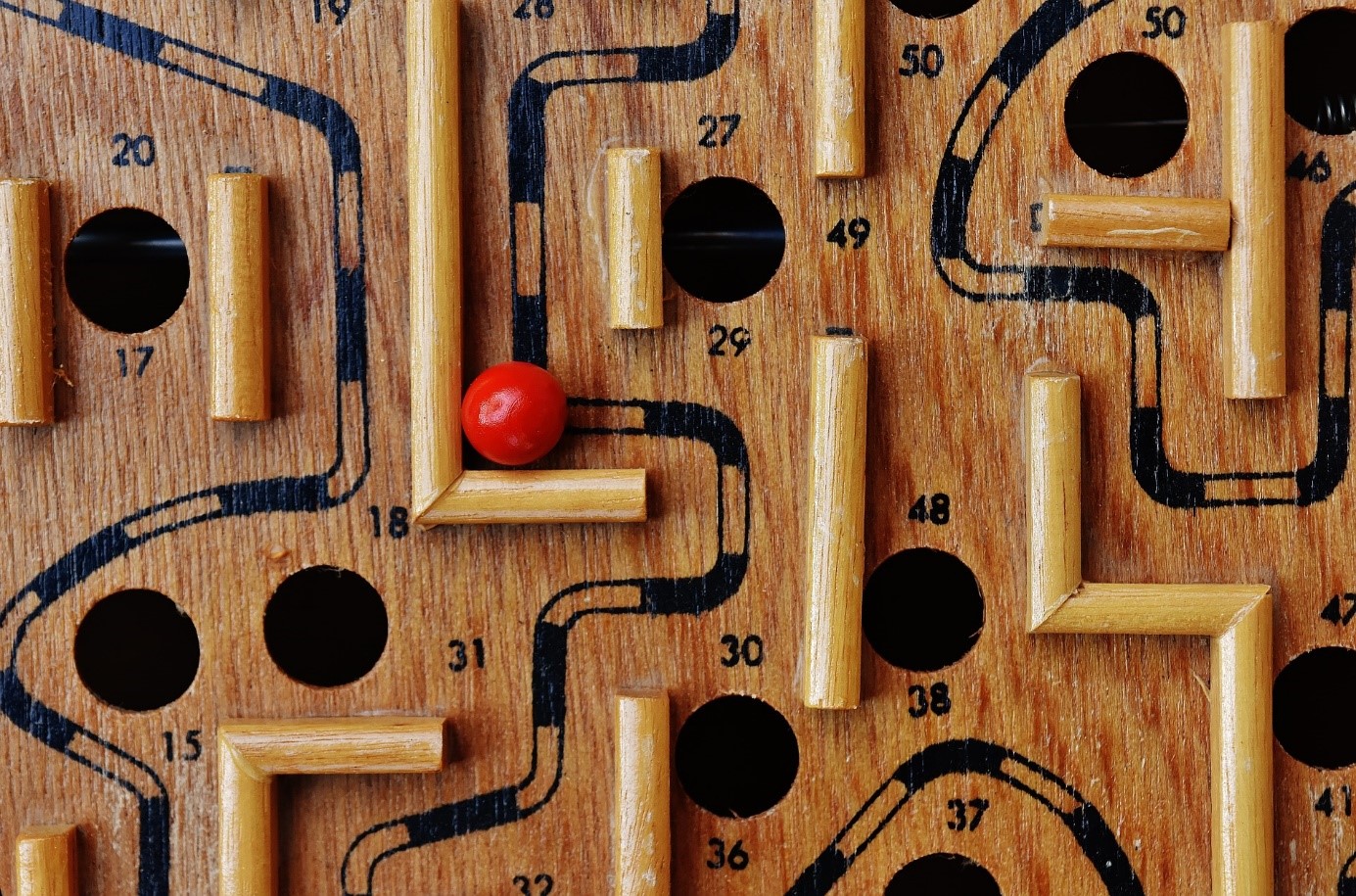

This is when the institutional entrepreneurs and navigators enter the picture. I observed that there were agents able to navigate through the two university labyrinths, not only knowing the right people and communities, but especially knowing how to approach them. These boundary spanners were even able to translate between the languages of the different counterparts and therefore intermediate between communities and stakeholders. So, instead of focusing on the number of university entry points, maybe what we really need to think about is how to find and mobilise the right boundary spanners?

Who am I and why am I thinking about this? Find out here